This post was imported from my old Drupal blog. To see the full thing, including comments, it's best to visit the Internet Archive.

Disclaimer: As usual, this post contains my personal opinion and does not reflect that of any organisation with which you might associate me.

The other day, I had a lovely conversation with some folks from the BBC about some of their future plans. In the course of the conversation, Michael Smethurst spoke about his frustration when dealing with people involved with particular programmes at the BBC, where every single one of them thinks their programme is a “precious snowflake”, completely unique, that simply can’t be treated in the same way as all the other programmes described on the site.

Michael’s point, of course, is that TV programmes have a hell of a lot of similarities with each other. They all have episodes and cast members and may have trailers or be available on iPlayer. When the BBC models them in the same way, they gain enormous efficiencies in their ability to store and access information about programmes: they can reuse code, share content between programmes, and perform analyses over the aggregated data set. It’s great for users too: they get the same fantastic user experience no matter which programme they are viewing information about, and can apply the experience they gain when navigating pages about one programme when they need to find information about another.

The ability to classify and categorise, to bring order to what seems like chaos, to create a model of the world, is one of the things that marks humans from animals. We can look at a hundred people, with different colour hair and skin; different height and build; smiling, talking, crying, and still call them all Person because the essential characteristics that govern how we interact with them are the same.

But if there’s one thing that the last five long, hard years working with legislation has taught me, it’s that in any vaguely interesting domain, this search for order will always fall down in the face of reality.

Surely, I thought in my naive early days, every piece of legislation is uniquely identified through its type, calendar year, and number? Not so! There are six items for which this is not the case, because prior to 1963 legislation was numbered based on the year of reign of the monarch rather than the calendar year.

Surely the year that is used to number legislation is dependent on the date it is made and written into law? Not so! Sometimes departments forget to register legislation they make until the following year, so it is numbered the year after it’s made.

Surely an item of legislation can only make changes to legislation from the day it is written into law? Not so! There is, rarely, legislation that rewrites history: that says other legislation should always have had different content to that which was originally written.

It has come to the point where I never (hah!) make any statements about legislation of the form “X never happens” or “Y is always true” because there is always, always, an exception.

What this has taught me, as a developer, is the power and necessity of escape hatches. For example, templating languages that provide a method of escaping to code are so much more valuable than those that do not. Similarly, I favour strongly, in the technologies that I use, the ability to extend a common data structure, be it through data-* attributes in HTML, through generic elements such as <span> and <div> or through the essentially open-ended nature of RDF as a data model.

It has also given me a very different view of the world to Michael. Because when you accept that there are always exceptions, you do not see snowflakes as merely crystals of water, but as exceptional, beautiful and, yes, immensely precious.

And this is why I love the web. The web does not force every site to have the same structure or the same look and feel. It does not insist on consistency; it has space for every quirk. And it proves beyond all doubt that it is possible for all these precious snowflakes to exist in a single, global, interlinked information system in which people manage to find not only the information that they need, but also community and connection with each other.

Inside Government

So it is with these eyes that I look at the new Inside Government pages on the gov.uk site and am frankly horrified. Because we’re not just talking about a BBC programmes here, but about powerful institutions, many of them decades if not centuries old, that lie at the very heart of government and how our nation is run. And each of them is relegated to a subfolder of a subfolder of a subfolder, their unique histories and approaches and goals expressed through three pictures on a carousel.

It feels like some kind of Orwellian nightmare: the relentless focus on user needs leading to a future of identikit pages, with no individuality, no character, no clue that behind these pages – which, remember, under the Single Government Domain policy becomes the single authoritative view, the site that represents the department on the web – is a living and breathing institution that manages hugely important parts of our lives. A future in which what each department says and the way that it says it is governed through the Government Digital Service (GDS), in Cabinet Office, the hand of the prime minister. And now we’re talking about local government too?

Let us just look at one example. Last September, William Hague gave a speech in which he described the hollowing out of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) by the previous government, a process that scrapped its language school, closed embassies and destroyed its library. He said:

Strong institutions are necessary in civil society, to encourage participation and keep in check an overmighty State; they are necessary to our judiciary and Parliament so that the law is upheld and the making of it respected; but they are also necessary within the State, a point tragically overlooked by those Prime Ministers who have created and abolished departments on a fancy or a whim, destroying as they did so the pride and continuity of thousands of public servants while rendering government incomprehensible to the average citizen. The whole country should know what the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is and what it does, and all those interested in foreign policy at home or abroad should see it as a centre of excellence with which they aspire to be associated.

For most UK citizens, the only point of access to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office is its website: they will not visit King Charles Street, nor any of the UK’s embassies. The department’s web presence is the only way that it makes itself, and its unique role, comprehensible to the average citizen, the only method of letting the whole country know what the FCO is and what it does. And they have content that is completely unique to them: a database of Treaties, a hugely rich set of information on travel and living abroad and a wealth of historical information about the Foreign Office. This simply doesn’t fit in a model of a department as a set of Ministers, Policies, Publications and so on. And if it doesn’t fit, will it simply be excluded, lost from its website like its language school, its embassies, its library?

I could have picked any government department here – each one has its unique characteristics and content – but Hague articulates the case around FCO so well. His message is not the expression of a simple conservative impulse to resist change and preserve the status quo, but about maintaining the integrity of an institution’s identity and independence to encourage participation and keep in check an overmighty State

. If we believe in Open Government, Open Democracy and the power of the web to enhance civic engagement then we must, surely, enable each of these institutions to have their own independent voice on the web.

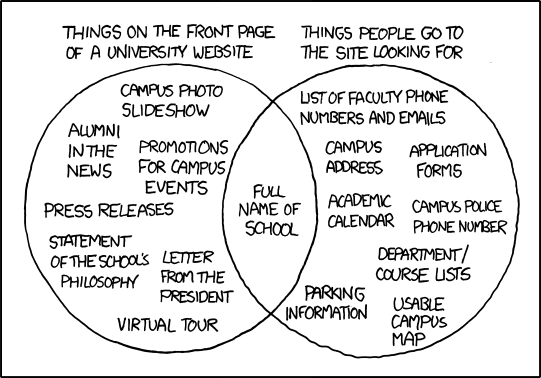

I am reminded of the XKCD:

The two sides of this Venn diagram illustrate two approaches to building a website for an organisation. On the left is the website as an expression of the identity of the institution, on the right the website as a means of satisfying the reason the user originally visited the site. My argument is not that the right side of this diagram is unimportant – in fact I believe it is absolutely essential – but that an institution’s website must cover the entire space: it must provide a mechanism for self-expression as well as catering for its user’s requirements. To enhance civic engagement, we do not need to simply answer the query that led the user to the site, but to encourage and lead them on to see more about the institution that has provided the answer.

It is only the institution itself that knows the self it wants to express, and because the real world is complex and organisations are unique, that self will not fit into any model that we devise. News, Policies, Consultations – of course these are all important to all departments, but they are the tip of an iceberg. Look at the space that FCO devotes to its history on its website: this shouts to the world the kind of reliable, solid and flexible organisation that they are and want to remain. Compare how DECC devotes space to statistics, emphasising its adherence to transparency and evidence-based policy. Self-expression is so much more than changing logos or backgrounds, more than having different content on an About page, it is about making space for the things that are important to you.

“But but but!” I know the arguments. We must cut costs, stop the uncontrolled proliferation of government websites; we must improve the quality of the government’s presence on the web, present a unified view, make it easy for users to locate content without knowing where to look. The vision we see expressed through Inside Government is but the natural conclusion, the end of that slippery slope. But it is the great slippery slope fallacy that everything must be taken to its natural conclusion, that because 750 websites is too many, one is enough.

Possibly the biggest irony of the gov.uk beta is that while it is delivering a Single Government Domain – everything is to be found under www.gov.uk – it does not seem to address the core reason stated for providing it. In Martha Lane-Fox’s letter to Francis Maude, which kicked off this whole endeavour, she said:

Government publishes millions of pages on the Web, via hundreds of different websites. Most of these sites are still run as silos within departments. This fragmentation leads to significant duplication of functions and technology, and means the overall user experience is highly inconsistent.

Try searching for ‘Single Government Domain’ on the main gov.uk site or for driving test centres on Inside Government. The searches do not work (though Inside Government does give you a link that enables you to search the other silo). The result pages are completely different in feel except for the top and bottom banners. The page on Arrest and Imprisonment Abroad mentions but does not link to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office’s page. Yes, yes, I know that it’s still beta, but these things lie at the heart of the stated rationale for a Single Government Domain: is this the extent of the consistency and integration that we are aiming for?

Yes, it is, because the Single Government Domain policy was never truly about either of these things. Read Martha Lane-Fox’s letter again carefully (my emphasis):

No1O feel it is preferable to go from 750 top level website domains (eg www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk) to a single top level website domain for all of central government.

The Single Government Domain policy, indeed GDS itself, is about control. It is “we will do it for you”, not “we will help you do it”. It is about managing the output of institutions that might keep in check an overmighty State

. It is anti-web and it is anti-democracy and I cannot remain quiet about it any longer.

To my friends at GDS: I respect and admire you all. You are incredibly talented and able to do amazing things. You have behind you a level of financial and political support the like of which most civil servants will never see. I know you have joined GDS not just to do work that you love but to do good for the country. This is my plea to you: find a way to avoid this vision. Nurture the exceptions. Give institutions their voice. Treat them as precious snowflakes.