This post was imported from my old Drupal blog. To see the full thing, including comments, it's best to visit the Internet Archive.

As part of the TAG’s work on httpRange-14, Jonathan Rees has assessed how a variety of use cases could be met by various proposals put before the TAG. The results of the assessment are a matrix which shows that “punning” is the most promising method, unique in not failing on either ease of use (use case J) or HTTP consistency (use case M).

In normal use, “punning” is about making jokes based around a word that has two meanings. In this context, “punning” is about using the same URI to mean two (or more) different things. It’s most commonly used as a term of art in OWL but normal people don’t need to worry particularly about that use. Here I’ll explore what that might actually mean as an approach to the httpRange-14 issue.

Note: The material here is a summary of what I think is the best way forward following various discussions within and outside the TAG, in particular with Jonathan, Henry Thompson and TimBL. Not all these people agree with or endorse the approach described here, but neither do all the ideas in this post originate from me.

Background

Five things recently make me more convinced than ever that the TAG must either provide some direction to the community, and soon, or get out of the way.

-

The proposed Linked Data Platform Working Group charter and the Submission that is the main input to the group specifically brings together linked data and REST, and the only mention of

303redirections so far is to do with paging. -

A recent thread on the W3C public-vocabs mailing list, raised the question of whether to embed schema.org markup about the page itself within a given page, or only about the thing that the page is about. I wonder how many pages are being described as

schema:WebPageas well as things likeschema:Organisation, and how people choose which class to use. -

The initial version of Dan’s proposal for handling external enumerations within schema.org talked about minting new URIs in the

ext.schema.orgdomain specifically to proxy existing URIs so that they can be guaranteed to provide the right (303) HTTP response. I can see the reasoning (persuading people to use303redirections is difficult) but it would be frustrating if the end result were a centralisation of the URI space. -

Talking with my colleague John Sheridan about updating the UK government’s guidance on Designing URI Sets for the UK Public Sector, I really don’t know what to advise. Should the guidance continue to be to use

303redirections, when I know from experience that these can be impractically slow? Should it change to recommend using hash URIs to identify things? -

The very first message on the Technical Architecture Community Group was in part about how to identify people with URIs.

Of course the httpRange-14 issue has been running for so long now that I’d estimate that currently 80% of the discussion about it is meta-discussion about whether there it needs to be discussed, how much it should be discussed, how to raise the quality of the discussion, how anyone who discusses it is a time-wasting idiot and should just shut up and so on. It’s a terrible destructive cycle: the more this goes on, the higher the proportion of time being spent on the meta-discussion, and the longer any discussion takes.

But I believe that we can get to a point where we don’t have to discuss it any more (except to reminisce about what a waste of time it was), and I believe that the only way to get to that point is for the TAG to push through and provide a practical way forward.

Terminology

Let’s start off with some terminology. The basic scenario is a three-way interaction between three agents:

- a supplier who manages the information that is accessible at a URI; it’s worth noting that the supplier for a particular URI might change over time and what exactly is provided at a URI is controlled by multiple parties, as there may be many service providers involved in routing the resolution of a URI, others in constructing what’s shown on the page served from the origin web server, and still others who transform that content en route to the consumer

- a third-party publisher who publishes some information about a URI; unlike the supplier, they generally have no control and incomplete knowledge about the information available at a particular URI, its stability over time or consistency across representations

- a consumer, typically an application of some kind, who has discovered the information published by the supplier or third-party publisher and wants to do something with it

It’s also useful to include terms for three things that are passed around or referenced during the interaction, which are defined with the URI specification and HTTPbis. (The current HTTP specification, RFC 2616 is also of interest, of course, but HTTPbis is a better reflection of current practical use of HTTP, and is close to complete, at which point it will replace RFC 2616.)

- a URI which is a string of characters matching the syntax in the URI specification that identifies a resource; we only care about

http:URIs here, although similar considerations may apply to URIs that use other schemes - a resource which is identified by the URI; the debate over whether HTTP constrains the nature of the resource is at the heart of some discussions around httpRange-14; here, as in the URI specification and HTTPbis, a resource could be anything

- representations which are media-typed sequences of bytes (often characters) encoded within the response to an HTTP

GETrequest on a given URI; per HTTPbis, the response to aGETrequest contains a representation of the current state of the resource identified by the URI

Content and Meaning

Now I will introduce a few new terms that aren’t used in the URI specification of HTTPbis but which are useful for discussion.

- The content located by a

http:URI is whatever core information a consumer interacts with through the HTTP interface provided by the server for that URI. This is the information that is common across all the representations that are returned through aGETon a given URI (through content-negotiated variants). We can say that thehttp:URI locates the content of the resource that it identifies, because you can get hold of the content of a resource by performing an HTTPGETrequest. - The sense referred to by a

http:URI is a social construct that arises from the properties associated with the URI by publishers and the way that these invoke action in consumers. We can say that ahttp:URI refers to a sense. While you canGETcontent from a URI, determining its sense can only be achieved by examining the way in which the URI is used within data published on the web. The sense referred to by a URI might vary in different contexts, but equally a single sense may emerge in the use of the URI. One sense referred to by a URI may be its content, and for some types of information that may be the only sense referred to by the URI by anyone.

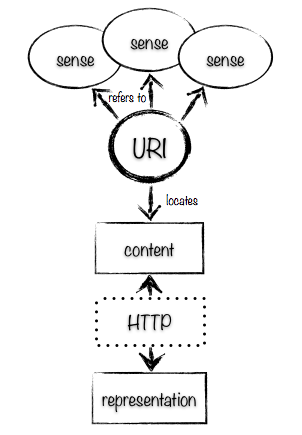

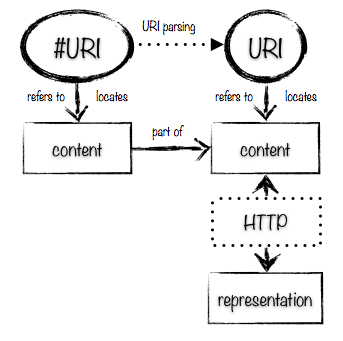

Here is a diagram that shows how these different terms hang together.

For example, take the URI http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B004TRXX7C. The content located by this URI is the core information in the web pages we GET from the URI. The sense referred to by the URI could the same as the content, or it could be the novel Moby Dick, or the particular Kindle edition of the book. We can’t tell from any interaction at the level of the HTTP protocol what the sense of the resource is: that information has to come from the application level.

Like the meaning of a word, the sense that a URI refers to is a social understanding which emerges from use of the URI across the web, and a given URI may be used to refer to different senses in different sources of information or over time. Consumers interpret the information that uses a URI and is made available to them on the web in order to draw conclusions and perform a task. Different consumers will have different levels of trust in the particular interpretation of the URI that a given publisher provides; in particular, the information published by the supplier of the URI might be given a higher weight than that from third-party publishers. Tools like sig.ma illustrate how information can be combined from multiple sources with different weights, by associating metadata about the location of the data with the data itself; unpicking commonalities between groups of sources may help to work out the different senses referred to by these different sources.

The content located by a URI is more concrete, and is important because certain classes of application may infer something about what they can do with the content found at a given URI based on information published about the URI. The canonical example of this is a consumer that searches the web for public-domain pages, based on information published about the licensing of those pages, and displays a portion of one each day within a feed. This application can’t work properly if it doesn’t know what actual content is public domain. In the Amazon example above, if there is a statement saying http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B004TRXX7C is public domain (referring to the novel “Moby Dick”, which is one possible sense referred by the URI, one on which the copyright has expired), a consumer that assumes the URI is being used to locate the content at that URI will assume that the representation retrieved through a GET on that URI is public domain. The consumer might pick out the first major paragraph from the HTML page for display, but that first paragraph is actually an editorial review that is marked with a separate copyright which therefore shouldn’t be displayed in a feed of public-domain content.

Of course interpreting assertions made by publishers about particular content can be just as complex as interpreting statements about a particular sense of a URI, especially when those assertions come from a third party. The content located by a URI may change over time, and potentially in dramatic ways if the domain name of the URI changes hands, so any statements that a consumer discovers about content needs to be assessed by a consumer in that context. That said, while the validity or truthfulness of a given piece of information about content may be variable, the bytes that are located through a URI by a consumer are tangible and discoverable in a way that the sense referred to by a URI can never be.

The core disagreements around httpRange-14 arise from whether you view the content located by a hash-less http: URI which provides a successful (2XX) response to be the only valid sense referred to by that URI, or whether you think they could be different things, and if you think they can be different things then which of those you think the URI identifies when it is used.

Current State

The URI and HTTP specifications talk only about URIs identifying resources and being able to make requests using URIs to get a representation of the resource, they do not talk about senses or content.

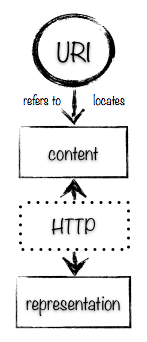

The httpRange-14 decision is based on a design where if you can successfully GET a representation using a URI (ie you receive a 200 OK response) then the sense referred to by the URI is the content located by that URI. This is pictured in the diagram below.

Sometimes, a server simply doesn’t store the content for something that it wishes to provide information about (for example, the Amazon website doesn’t store the content of Moby Dick), and sometimes the sense that a publisher wishes to confer on a URI is such that no content can be transmitted over the wire, such as a Person. In these cases, under this design, the server cannot give a 200 OK response because it does not have the content for the URI. There are then two patterns a publisher can use to assign a http: URI to something in these cases.

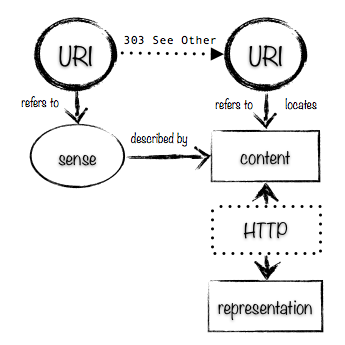

One pattern is to use a 303 See Other redirection to a URI whose content (which is the only sense of the URI in this design, remember) describes the original URI. This is pictured below.

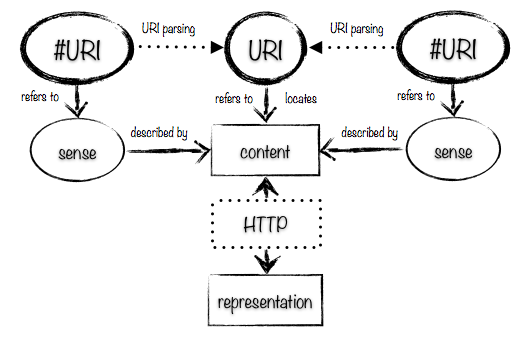

The second pattern is to use a hash URI. This gives a very similar pattern, as you can see from the diagram below; the only difference is that instead of following a 303 See Other redirection to get from one URI to the other, you can use URI parsing: you chop off the fragment part of the URI and perform a GET on the resulting URI to get a description. Often this leads to several hash URIs being described by the same content, as illustrated here:

However, hash URIs are also used to identify fragments within pages, which are bits of content. For hash URIs that identify fragments of a page, the picture looks more like this:

A consumer can’t tell just from looking at a hash URI whether it identifies a fragment of content or is being used to refer to something described by the content located by its base URI: the consumer has to make a request and understand the fragment identifier as it applies to the media type of the representation that it gets back. Also, if there’s any content negotiation going on, even if the fragment identifier doesn’t make sense for the media type, or doesn’t locate a fragment within the representation that the consumer retrieves, it might still locate a fragment of content within a different representation of the resource than that the consumer has retrieved.

In any case, common usage of hash-less http: URIs differs from this model of content and sense being one and the same for all URIs that give a successful response. Often URIs are used in data formats such as JSON, XML, RDF or HTML where the content and the sense of the URI are different things. For example, on the Flickr the content located through the URI http://www.flickr.com/photos/45701084@N08/7051652969/ is a landing page that provides a bunch of information about an image, but the data within the page includes a statement about its license:

<http://www.flickr.com/photos/45701084@N08/7051652969/>

cc:license <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en> ;

.

in which that same URI refers to the photograph itself: the sense referred to by the URI. The only way that you can tell this is by being a human: reading the page and the context in which the text describing the license is used.

This mismatch between the design specified by RFC 2616 and the httpRange-14 decision, and practice on the web today results in arguments back and fro with people saying, in essence, that the resource a URI identifies is the sense conferred by the URI’s supplier, or that a URI should always be taken as identifying the content of the resource, and then discussions about how to signal to an application that in particular cases the supplier really does mean the URI to identify some content or really does mean the URI to identify a particular sense, and if so which sense is being referred to.

Punning

“Punning” approaches attempt to cut through these disagreements by saying that the context in which the URI is used determines whether it is locating content or referring to a sense.

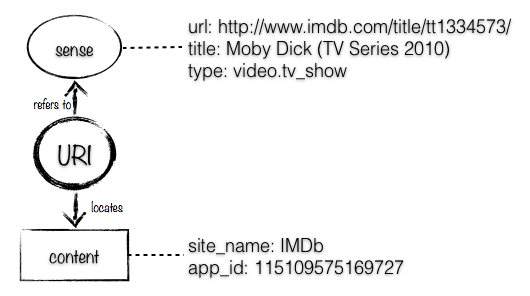

If we look at some Open Graph Protocol (OGP) statements on http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/, we see:

<meta property="og:url" content="http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/" />

<meta property="og:title" content="Moby Dick (TV Series 2010)"/>

<meta property="og:type" content="video.tv_show"/>

<meta property="og:image" content="http://i.media-imdb.com/images/SFc0774313bf9ccbfe22050c8bb4029e41/imdb-share-logo.gif"/>

<meta property="og:site_name" content="IMDb"/>

<meta property="fb:app_id" content="115109575169727"/>

Some of these properties – the url, title, type and image – are about the Moby Dick TV Series – the sense referred to by the URI http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/. Others – the site name and Facebook application id – are about the content located by the URI. The properties that are provided by this data are all related to the same URI, but they aren’t all properties of the same thing. In natural language we might say:

- a URL of the thing described by the page is

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/ - a title of the thing described by the page is “Moby Dick (TV Series 2010)”

- a type of the thing described by the page is “video.tv_show”

- an image of the thing described by the page is the content at

http://i.media-imdb.com/images/SFc0774313bf9ccbfe22050c8bb4029e41/imdb-share-logo.gif - the site of the page is IMDb

- the Facebook application to use with the page has the identifier 115109575169727

The property itself determines whether it applies to the content located by the URI (the page) or a sense referred to by the URI (in this case, the thing the page describes). Here’s a diagram that shows the distinction:

Defining URI Usage

The way in which a URI is interpreted – as referring to a sense or locating content – is dependent on where it is used. In XML, for example, an xmlns:* attribute contains a URI; when this is a hash-less http: URI, this refers to an XML namespace (a sense of that URI): it doesn’t matter what content you GET from dereferencing the URI, or even if it can be dereferenced at all. On the other hand, the href attribute on a xi:include element defined by XInclude is used to locate some content to be included within the referring XML.

It is really up to the format in which data is encoded to determine how the URI should be interpreted: as locating some content or referring to a sense. As with interpreting any information with which it’s presented, an application that needs to work out which is meant might use:

- built-in knowledge (eg an application might know that the

og:titleproperty is always about the sense referred to by the subject URI, based on documentation about the property [this is essentially the same as if the information were embedded within a schema, but without the implication that every application must download and interpret a schema every time it happens across a property]) - information encoded within a schema (eg a schema might classify the

og:titleproperty as aPropertyWhoseSubjectIsTheSubstanceOfAResource) - a default for the format of the data (eg given OGP uses RDFa, RDF could specify that by default URIs refer to a sense, and therefore barring other information to the contrary, properties cannot be assumed to be about the page itself)

- a default for the web (eg we might say that barring overriding information, all hash-less

http:URIs are assumed to locate content, as this is consistent with the current definition of HTTP in RFC 2616)

Thus an implication of this approach is that the people who define languages and vocabularies must specify what aspect of a resource a URI used in a particular way identifies. There are four possibilities for a given URI:

- the URI is being used to locate some content

- the URI is being used to refer to a sense

- the URI is being used to identify either content or sense but it’s not specified which

- the URI is being used to both locate content and refer to a sense (ie a property applies equally to both)

Equality

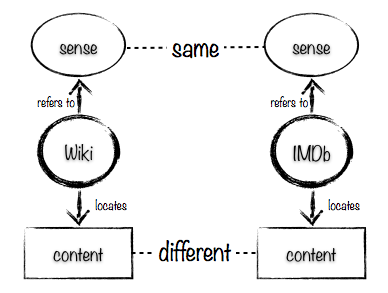

Now let’s consider what happens when there is more information available about something, but it uses a different URI. The page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries) is about the same TV series as http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/. Imagine that this similarly made available the information that it held using OGP. It might contain:

<meta property="og:url" content="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries)" />

<meta property="og:title" content="Moby Dick (miniseries)"/>

<meta property="og:type" content="video.tv_show"/>

<meta property="og:site_name" content="Wikipedia"/>

The two pages describe the same thing: the sense referred to by the two URIs is the same. However, the content of the two pages is different. If you simply smushed the properties together, ignoring the fact that some properties apply to the content and others the sense of the resource, you’d get some data that wasn’t quite right:

{

url: [

'http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/',

'https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries)'

],

title: [

'Moby Dick (TV Series 2010)',

'Moby Dick (miniseries)'

],

type: [

'video.tv_show'

],

image: [

'http://i.media-imdb.com/images/SFc0774313bf9ccbfe22050c8bb4029e41/imdb-share-logo.gif'

],

site_name: [

'IMDb',

'Wikipedia'

],

app_id: [

'115109575169727'

]

}

Having two URLs, two titles and so on is fine, but having two site names doesn’t make sense: the og:site_name property is related to the content located by the URI, and the content is different for the two URIs. This is illustrated below.

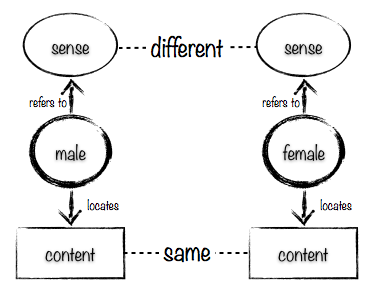

Conversely, imagine a situation in which there is a single document on a web server that is served up from the two URIs

http://example.org/gender/male

http://example.org/gender/female

In this case, the content located by the two URIs is exactly the same, but the sense referred to by the two URIs is different: one refers to the gender ‘male’ and the other to the gender ‘female’, as illustrated here.

So there are three types of equality that we have to be concerned with:

- equality between the desired sense and content of a single URI, as described earlier

- equality between the senses referred to by different URIs

- equality between the content located by different URIs

In general equality between the resources identified between two URIs is a controversial thing to assert, because different contexts may refer to different senses of a particular URI, some of which may be equal with a sense referred to by another URI and some not. Like any statement made about URIs, the source of statements about equality must be considered.

Formats that wish to make assertions about equality between resources should provide ways of saying that the sense referred to by two URIs is the same, without implying that the content located at those two URIs are the same, and vice versa, and to assert that the sense and content of a URI are equal. What these properties are – how exactly these kinds of equality are asserted in a given format – is up to the format, but it’s important that the properties are kept distinct to enable people to articulate the full range of equality relationships between resources.

Implications for Linked Data

I have tried to keep the description above neutral in terms of technology choice, because I believe that the issue of how to interpret URIs within data is common across all languages that use URIs. However, as I’ve discussed previously, linked data is particularly affected by these issues both because URIs form a central part of the way it works as a data format and because culturally the community tries very hard to adhere to “good web architectural practice” in the hope that this will confer long-term benefits.

For that reason, I’ll look at what I think the impacts are on linked data practice of using the “punning” approach that I’ve described above.

RDF

The definition of RDF is currently in flux, as RDF 1.1 is developed, so now is a good time to consider its use of URIs.

RDF itself is not particularly concerned with what URIs identify: it is simply a model that can be used to associate properties between “resources”, where in the RDF context this term means anything that can be the subject or object of an RDF statement, including literals. (RDF’s use of the term “resource” is not the same as that used in the URI specification or HTTPbis.) The only real limitation in RDF 1.0 Concepts, is that a hash URI identifies something described by the RDF/XML representation retrieved when the URI is resolved. In the current Editor’s Draft of RDF 1.1, the same section is less specific about what such a fragment might denote. So if the language and concepts above were adopted, RDF 1.1 should be more careful in its use of terminology, and attempt to be consistent with the URI and HTTP specifications, but I don’t think anything fundamental needs to change in the core semantics of RDF.

Vocabulary Designers

Under the “punning” approach, the property used within an RDF statement determines how the URI given as its subject or object should be interpreted. A consumer that discovers a URI by looking at the properties associated with it needs to be able to tell from the properties themselves whether it can associate those properties to particular content that it locates by requesting the URI or not.

Some properties have a defined domain or range that precludes the property from being used to annotate content. For example, the foaf:nick property has a domain of foaf:Person, and a foaf:Person cannot be a web page. Given this domain, an application can tell that the URI http://www.jenitennison.com/ used in a statement such as:

<http://www.jenitennison.com/>

foaf:nick "JeniT" ;

.

cannot be being used to locate the content of http://www.jenitennison.com/, even if http://www.jenitennison.com/ responds with a 200 OK response.

Note that this inference doesn’t work the other way around. The property cc:license has a domain of a cc:Work but without additional information about the property an application could not infer that in a statement such as

<http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B004TRXX7C>

cc:license <http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/> ;

.

the URI http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B004TRXX7C was being used to locate the content of http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B004TRXX7C: it could equally be being used to refer to some sense of the resource (for example the novel Moby Dick).

To support “punning”, therefore, RDF vocabulary designers would need to have additional properties that could be applied to RDF Properties to indicate how their subject (and object where applicable) should be interpreted. For example, the Creative Commons vocabulary might include (warning: made up property names and instances):

cc:license

rdfs:subjectUri rdf:sense ;

rdfs:objectUri rdf:content ;

.

with the implication that URIs used as the subject of cc:license should be understood as referring to the sense of the URI, while those used as the object of cc:license should be understood as referring to the content retrieved from the URI.

Even if properties like rdfs:subjectUri or rdfs:objectUri are defined, there are going to be RDF properties for which the interpretation of subject and/or object URIs isn’t specified, and thus consumers of RDF content need to have a default interpretation. What that should be is, I think, a matter for the RDF community to decide.

Inference

The major difficulties with the “punning” approach and the current use of RDF comes when reasoning is used across RDF statements in which the same URI is used in different ways, particularly with properties where the interpretation of the subject and/or object isn’t specified.

For example, if a consumer finds the following triples at http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/:

<http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/>

og:url "http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/" ;

og:title "Moby Dick (TV Series 2010)" ;

og:type "video.tv_show" ;

og:image "http://i.media-imdb.com/images/SFc0774313bf9ccbfe22050c8bb4029e41/imdb-share-logo.gif" ;

og:site_name "IMDb" ;

fb:app_id "115109575169727" ;

.

and the following triples at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries):

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries)>

og:url "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries)" ;

og:title "Moby Dick (miniseries)" ;

og:type "video.tv_show" ;

og:site_name "Wikipedia" ;

.

and then the assertion:

<http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/>

owl:sameAs <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries)> ;

.

then the result of inference will be that all the statements made about http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/ apply equally to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries), which is not the case.

To enable publishers to make assertions about equality of sense and equality of content separately, we will need new relationships. For example:

<http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/>

owl:sameSenseAs <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries)> ;

.

would only infer that those properties whose subject is the sense of http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/ apply equally to the sense of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moby_Dick_(miniseries). A owl:sameContentAs property could similarly assert equality between the content of two URIs.

The impact is not limited to reasoning with owl:sameAs: all inference in RDFS and OWL is based on the assumption that a single URI identifies a single entity. This works in situations where the RDF over which inferences are being made is all trusted (for example if it is all made available by the same publisher), and a lot of current use of OWL is precisely in these kinds of closed environments. The same inferences can be made even with information gleaned from the web at large, if that information is selected carefully.

Another approach, where publishers have mixed properties about the sense referred to by a URI and those about the content located by a URI is to pre-process those RDF statements to create separate (blank node) RDF resources. For example, if og:url, og:title, og:type and og:image are defined to have a subject that refers to the sense of the URI, and og:site_name and fb:app_id to have a subject that locates the content of the URI, the statements about http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/ above could be translated into:

_:imdbSubstance

rdf:senseUri "http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/" ;

og:url "http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/" ;

og:title "Moby Dick (TV Series 2010)" ;

og:type "video.tv_show" ;

og:image "http://i.media-imdb.com/images/SFc0774313bf9ccbfe22050c8bb4029e41/imdb-share-logo.gif" ;

.

_:imdbContent

rdf:contentUri "http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1334573/" ;

og:site_name "IMDb" ;

fb:app_id "115109575169727" ;

.

Here, the (putative) rdf:senseUri property is an inverse functional property that provides the URI for which the individual is a sense, and the rdf:contentUri property is an inverse functional properties that provides the URI for which the individual is the content.

This separation would then allow existing inference to take place on the separate entities.

Publishers

There are many advantages offered by the “punning” approach for linked data publishers:

- it supplies an easy on-ramp for suppliers who want to annotate their pages with HTML data such as RDFa and microdata: suppliers can use URIs that they already support to refer to things other than documents, if they choose to, which means all they need to do is add metadata to their pages (as they are currently using OGP and schema.org)

- suppliers do not have to have access to server configuration in order to promote the use of particular URIs to mean things that do not have content (such as people or organisations)

- publishers can copy and paste URIs from the location bar of their browsers (a familiar activity for people who wish to provide a pointer to something) rather than inspecting pages for a recommended URI to be used to refer to a particular sense

- organisations such as schema.org can easily recommend the reuse of URIs published by other people, such as Wikipedia, without requiring those publishers to alter their server configuration or requiring developers that use schema.org markup to add fragment identifiers to their URIs

- explicit

describedbyanddescribeslinks can be made between URIs rather than using an HTTP status code where necessary; these can be incorporated directly in data and do not require a network connection to be discovered

Provenance

The “punning” approach that I’ve described here has as its core the recognition that different consumers will trust different sources of information to different levels. Knowledge of the provenance of a particular source of information is one way in which consumers can work out what to trust and how to resolve conflicts sources.

The work of the Provenance Working Group is important here both in identifying the provenance of particular content located at a given URI and in providing a vocabulary for describing the processing that a consumer performs to retrieve and process that content in order to extract data from it (for example, the time of the retrieval and the HTTP headers used may lead to the consumer receiving different content; the particular version of software used may lead to different information being gleaned from that content).

Linked Data Platform

The particular issues around what URIs actually identify within RDF only become an issue when the URIs are resolved – when RDF is used within linked data. The new Linked Data Platform Working Group is a great opportunity to standardise around these practices, in collaboration with the other relevant working groups.

Final Thoughts

People use the terms “resource”, “identifies” and “representation” both within specifications and in common parlance as if there is a shared understanding of what they mean, when in fact different people use the terms in subtly but meaningfully different ways. This would be fine, except that the different understandings lead to different assumptions and engineering decisions, and friction for developers trying to build applications that publish and consume data whose assumptions differ.

We need to find a way forward that, even if not everyone’s ideal, is realistic, explicable and palatable. The “punning” approach that I’ve described above might not be it, but the analysis that Jonathan’s done of the various proposals and use cases suggests to me that it’s the closest we have. The main questions I have are:

- what use cases cannot be satisfied using this approach?

- what specifications would have to change if this approach was adopted, and would it be realistic to make those changes?

- what existing applications would break if this approach was adopted, and how might that breakage be mitigated?

At the very least, I hope that the vocabulary I’ve laid out in this post might be helpful in further discussions.

Of course any other comments are most welcome.