At the start of 2020, I wrote about community consent. I detailed some of the ways in which individual consent is failing, and why there’s a need for a more community-oriented approach to consent around the processing of data about people.

In the conclusion, I wrote:

Currently the media narrative about the use of personal data is almost entirely negative - to the extent that Doctor Who bad guys are big tech monopolists. Sectors, like health, where progress such as new treatments or better diagnosis often requires the use of personal data, are negatively impacted by this narrative, and can’t afford the widespread information campaigns that would shift that dial.

2020 wasn’t exactly the information campaign for community interests in data about people that I had in mind. But it has turned out that way: symptom tracking; testing, case, hospitalisation and death rates; research use of patient data; and mobility reports have become hugely significant as we navigate the Covid-19 pandemic. If nothing else, it has given us a set of examples to use when we talk about public benefit uses of data that everyone can relate to.

Community-level concerns are starting to be reflected at a policy level. For example, in July, an expert committee published a draft Non-Personal Data Governance Framework for India. Their definition of “non-personal” data includes anything that isn’t personally identifiable information (PII), which includes anonymised (de-identified) data about people. Their recommendations include defining data trustees to exercise community rights in this data.

The proposed European Data Governance Act is also significant in that it defines “data-altruism organisations” whose purpose is to make (usually personal) data available at scale for public good. The central idea is that people will donate data to these not-for-profits, who can then share it for research and other general interest purposes.

Population-level data

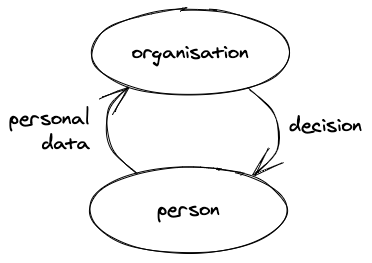

Salomé Viljoen’s paper Democratic Data: A Relational Theory For Data Governance really clarified for me why community interests are so important in an age of big data and machine learning. It tells a story of how existing data protection rights are built around the vertical relationship between ourselves and a data controller or processor. These made sense in a 1970s context, when an organisation (whether a bank deciding whether to grant you a loan or a government working out what tax you owe or benefits to give you) would primarily base their decision on what it knew about you and you alone.

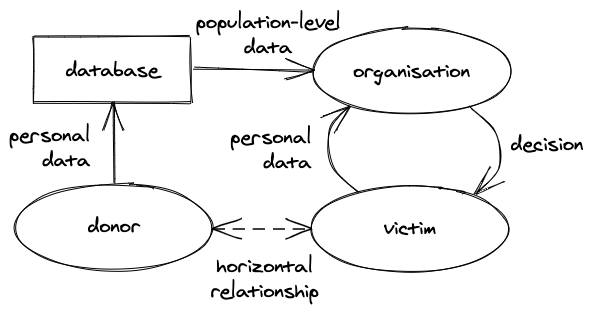

But nowadays, organisations make a lot more decisions using data, including much more trivial ones like what film they recommend you watch or what news and ads they show you. And these decisions are made using data about lots of other people as well as you: population-level data. As Salomé describes it, this sets up a horizontal relationship between a person affected by a decision (let’s call them victims) and the people whose data has also contributed to the results of that decision (let’s call them donors).

Economists have also started to recognise these effects. For example, Dirk Bergemann, Alessandro Bonatti and Tan Gan term this “social data” in their paper The Economics of Social Data. (I don’t particularly like “social data” as a term because it’s also frequently used to mean specifically data from social media usage, when these horizontal relationships can occur with data from other sources, such as financial or health information.) In economic terms, the use of data about me to make decisions about you is an externality: a cost or benefit imposed on a third party (you) without their (your) agreement.

The big drawback of individualistic models of governance over data is that the interests of donors and victims in the above diagram are not necessarily aligned, which means that individual donor decisions can adversely affect the victims and they have no say in the matter. In Salomé’s paper, she gives a couple of examples: a community maintained database of tattoos used to infer gang membership of someone who has never contributed to that database; and a water usage database set up to benefit poorer households suffering from water shortages, that richer households might refuse to contribute to because they won’t benefit from it. (In this latter case, the term “victim” is misleading, as they would benefit from data use rather than being damaged by it.)

It’s worth noting that in a lot of cases, personal data from victims is used both as input for a specific decision and stored within a database for use in future decision making about both them and other people. The two roles – donor and victim – get wrapped up with each other. But this is not always the case, and I think separating them clarifies what’s going on and the way suggested interventions might work.

Individual interests

Seen like this, there is a clear argument for data governance at a population level, to manage how population-level data is used to make decisions about victims. But there are still individual interests at play too.

First, while an organisation might make a decision based on data about lots of other people as well, most decisions about you will still involve them using some information about you, to personalise their results. For example, Netflix might recommend films that lots of other people like to you, but they will also use your viewing habits to work out which people have similar tastes to you, and favour their preferences in the recommendations it makes. A government might use data about other people’s job seeking experiences to work out how much support to give you, but they will still factor in your characteristics, such as your profession and how long you’ve been out of work. Your rights over the data about you that is being used to personalise the outcome of this data processing are still significant and important.

Second, you will have an interest in and rights over data even if it’s only used to make decisions about other people. You are affected by what and how data is collected (the chilling effect of surveillance). You are affected if there is a data breach. You might also feel responsible for and a moral obligation around the downstream uses of that data (leading to both data altruism and an urge to delete data so that it can’t be used in damaging ways). You might feel exploited if an organisation profits excessively from its use, leading to a call for profit-sharing or monetisation of data.

Considering these different sets of individual interests and rights separately might be useful when thinking about the shape of data protection regulations for personal data.

Community and collective interests

Community interests kick in whenever a community (whether a small group or a whole society) is affected by the use of population-level data.

Consideration of community interests is not new, and they are recognised in existing legal frameworks such as GDPR, at least when it comes to data held by the public sector. Under GDPR, personal data processing is lawful when it is necessary to fulfil a public task. These are defined tasks that are in the public interest as specified in law. The fact that they have to be defined in law provides democratic data governance over population-level data, in Salomé’s terms. Good examples are the census and data collected to monitor public health.

As Anouk Ruhaak described in her piece on collective consent earlier in the year, there are also a growing number of non-public-sector organisations that are specifically set up to steward and share population-level data. The data-altruism organisations of the EC’s Data Governance Act will be among them. At ODI, we would frame these as data institutions that steward personal data.

There are important decisions to make about how to govern these data institutions.

First, just as there are two sets of individual interests at play, as described above, there are also two sets of collective interests: those of the donors and those of the victims. These will not necessarily align with each other. For example, victims may want sufficient detailed data to be collected to make decisions more accurate; donors may want to minimise the amount of data that is collected about them, to reduce intrusive surveillance.

Second, there are different potential relationships between the set of donors represented in a database and the set of victims who are affected by a particular use of that data:

-

Donors and victims could be the same set of people, eg the use of data about Netflix customers by Netflix to customise its recommendations.

-

Donors could be a subset of victims, eg a biobank containing genetic data about a sample of the population, that is then used to draw conclusions about the wider population.

-

Donors could be a superset of victims, eg where population-level public health data is used specifically to identify and target vulnerable people with help and support.

-

Donors could overlap with victims, eg if the mobility patterns of some users of Google Maps – perhaps those people that use public transport – are used to draw conclusions about everyone who uses public transport.

-

Donors and victims could be different sets, eg if a facial recognition application trained on faces from one country is used to guess the emotions of people from another country.

Third, within each set of donors and victims there are likely to be divergent interests. It is in the nature of collective decisions they might not be in the interests of all the individuals belonging to that collective:

-

Donors will all naturally be concerned about the security of the data in the database. But they might have varying levels of concern about their obligations to contribute data over time (ie what and how data is collected about them); the value they receive in exchange for donating data (whether monetary, services, or a feel good factor); and the downstream uses of that data (different donors will find different causes more or less worthy). The mix of these concerns will change as new donors donate data into the database.

-

The set of victims will vary based on what the data is being used for: the population impacted by a particular set of decisions. Different sets of victims, generated by different sets of uses of the data, may have different interests. And within any given set of victims, there will likely be winners and losers – for example, if data is used to determine insurance premiums, some people who have to pay higher contributions and some who can pay lower ones – leading to different individual interests.

Data institutions stewarding personal data have to decide which of these varying sets of interests are going to take priority. For example:

-

A personal data store platform might choose to ignore the interests of anyone but individual donors, giving each donor the choice to opt in or out of particular uses, with each application therefore getting access to only a subset of a wider database. Victims have no control under this regime, although the information provided to donors to help them decide what to do could include information about victim benefits and protections.

-

A data union might be set up such that donors are a subset of victims – for example those Uber drivers who choose to donate their ride data into a joint dataset – with donors voting on uses of that data and assumed to represent the wider interests of all Uber drivers (victims). Sometimes these votes will result in outcomes that some donors are not satisfied with. The donors might not in fact be representative of the larger set of Uber drivers, and thus make decisions about the use of that data that favours them over others.

-

A biobank might be set up to have some decisions – such as the data collection process and the charges made for access to data – being made by donor representatives, while other decisions – such as who gets access to the data and for what purposes – are made by patient and public (victim) representatives. Both donor and patient/public representatives will need to exercise judgement about how they mirror the interests of the sets of people they are supposed to represent.

-

Most censuses are in a situation where the donors and victims largely overlap (they’re not quite identical because as time goes on, some donors die, they are no longer victims; as babies are born, decisions are made about them without them having contributed data – there are victims that were not donors). The interests of both – in particular weighing the intrusiveness and depth of the questions asked and the utility of that data – are balanced through democracy and consultation, and there will always be groups who are unhappy about the outcome.

Being explicit about whose interests are considered and prioritised through data governance is essential to avoid surprises. Promising both full individual control and public interest outcomes is likely misleading.

Final thoughts

A few random other thoughts that arise from this way of breaking down interests in personal data.

First, I think that recognising that individuals and sets of donors and victims have different, and sometimes conflicting, interests has implications for fiduciaries, such as the trustee of a Data Trust. As I understand it, a fiduciary is bound to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries that they represent. In many ways, they have less flexibility than we do as individuals to sometimes choose to sublimate our selfish interests in favour of others. So any fiduciary arrangement will have to be particularly specific about who is supposed to benefit. It would be useful, when discussing the benefits and drawbacks of fiduciary arrangements, to be explicit about the target beneficiaries as I believe different choices have different consequences.

Second, I wrote above that promising full individual control and public interest outcomes is likely misleading, but there are many fields – including public health medicine and opinion polling for example – where self-selected samples are sufficient and commonly used for drawing broader conclusions about a population. To make this work, you need to have a large enough sample; meet some minimum level of representativeness across important characteristics; collect enough demographic information to be able to weight and adjust data from different subgroups; and ensure anyone using the data has the statistical skills to do this adjustment to avoid faulty conclusions. (You also have to assume that the willingness to contribute data is not itself a correlate of the outcome you’re trying to understand or predict.) This implies that individual control and public interest outcomes can co-exist if you collect sufficient detailed and sensitive demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, location etc) to assess representativeness and do the necessary weighting. The characteristics that matter will vary by domain, as will the ease of collecting them. For example, demographic data is collected quite naturally in health, but still might be important but less likely to be gathered when looking at energy usage.

Third, in a fuller picture of rights and interests, there needs to be consideration of the interests of the organisations stewarding and using population-level personal data. There are costs involved in collecting, maintaining, securing and sharing data; there is income to be made from creating services and from automating decisions. These organisational interests aren’t necessarily aligned with the interests of donors or victims. I’ve focused on the interests of people, communities and society here, but it is necessary to think about organisational/private interests as well as public ones, and how they are balanced.

Finally, preferences around data governance arrangements are personal and political. I know I have a tendency to favour data governance that favours the victims rather than the donors, and collective control over individual control. So for example, I would look at the use of population-level data with society-level effects, such as micro-targeting of political advertising, and believe we need to have society-level governance (eg regulation via democratic government). I know others weight individual control and choice much higher than I tend to. This is one of the reasons why the design process for the data governance for a particular data institution (not just its operation) must itself be participative.

In summary, there seems to be growing recognition that our individualistic data rights frameworks are not on their own sufficient for dealing with population-level data, but there are still a lot of choices about what the alternatives look like. Thinking about patterns of data governance in terms of whose interests they promote – individuals or collectives, donors or victims – should help us to understand the consequences of those choices.