Publishing Information About Inward Links

In the Linked Data world, we talk a lot about having URIs that are identifiers for things, and making them HTTP URIs so that they can be dereferenced and people can find more information about those things.

This raises the questions of “what information should you publish?” Let’s make this concrete by using a real example: UK Legislation, which TSO is publishing for OPSI as Linked Data.

UK Legislation now has a set of URIs that are explicitly intended to be used as unique identifiers for items of legislation and parts, sections, subsections and so on within them. If you request one of these URIs, requesting RDF/XML, you will get some information about that bit of legislation, such as:

- bibliographic metadata such as its title, publisher, created date and so on

- links to other related sections or items of legislation

- links to particular versions of that bit of legislation

So we provide some basic information, and the links we know about, ie those within UK Legislation.

It turns out that lots of things aside from UK Legislation reference legislation, and that when you publish information about them it’s helpful to be able to point to the relevant legislation. For example:

- the Home Office relate offences to sections of legislation that state that a particular activity is illegal and has a certain maximum penalty

- local authorities are bound to provide certain services by law, so there’s a natural pointer from the definition of a service to that law

- administrative areas such as counties and local authorities are defined by law, so when the Ordnance Survey publish information about those areas, it helps to point to the law in which their names are legally defined as the authority on which their statements are based

- the publication of notices posted within the London Gazette is enforced by legislation, and the text of the notices usually indicates which piece of legislation caused the notice to be published

These are all inward pointers. As we publish information about UK Legislation, we won’t know about all these links to the information we publish. But people who access information about UK Legislation might well want to know about those links. Wouldn’t it be useful to know – given an item of legislation – what it makes illegal, what it compels local authorities to do, which administrative areas it defines, which notices it has caused to be published?

We were discussing the same issue the other day in respect of spatial objects. The Ordnance Survey, or other organisations peddling spatial data, may define spatial objects, but other people define the things that those spatial objects represent, such as schools, roads, parks and so on. It’s obviously useful to go from a school to the spatial objects that represent its buildings, but it would also be useful to go from a spatial object that is a school building to the school.

So what should we, as publishers, do about the inward links (that we know about)? When we publish information about something should we also try to publish information about the things that (we know) reference that thing? I think the answer’s “yes,” at the very least in any human-readable access we give to the information. And from that come two further thoughts:

-

If you are publishing data with outward links, it would be a good idea to provide feeds or other mechanisms that enable people to pull in basic information about the things that you’re publishing that link to something they’re publishing. SPARQL queries would do, but something a bit less general purpose and more approachable – I’m thinking a URL like

http://example.org/links?url=http://example.net/linked/resource– would be better. -

Information from another source is going to have different provenance/trust etc characteristics than the primary information you publish. That needs to be clearly indicated somehow; sounds to me like a requirement for named graphs.

Establishing Trust by Describing Provenance

Update 2009-11-08: The developers of the Provenance Vocabulary tell me that the pattern I used below isn’t correct, and there doesn’t currently seem to be a method of describing what I want to describe using that vocabulary. But it’s still under development, so hopefully it will become usable soon.

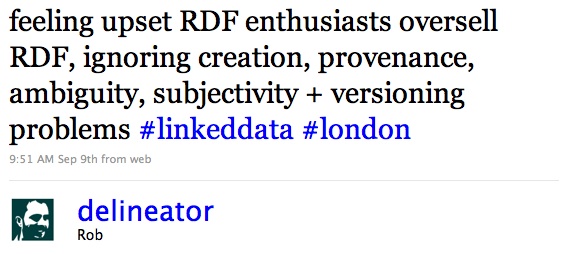

One of my favourite tweets from Rob McKinnon (aka @delineator) is this one:

because it’s one of the things that bugs me on occasion too, and because the issues he mentions are so vitally important when we’re talking about public sector information but (because they’re the hard issues) are easy to de-prioritise in the rush to make data available.

Expressing Statistics with RDF

Update: If you’re interested in expressing statistics in RDF, I’d encourage you to join the publishing statistical data group and take a look at the documentation for ‘SDMX-RDF’ described there.

One of the things that we’ve been discussing over on the UK Government Data Developers mailing list is how best to represent the vast quantities of statistical data that the government produces, in RDF. This is what we’ve come up with.

hmg.gov.uk/data and What We Can Do

This week, the Cabinet Office went live with a preview version of hmg.gov.uk/data, available only to those who subscribe to the UK Government Data Developers Google Group. Harry Metcalfe has written a great review, or of course you can check it out yourselves.

Already, though, there are discussions starting on the mailing list about how the data is being made available, and I’m worried that these might distract us from getting things done.

Resources for Values

When Leigh Dodds presented about Linked Data at the XML Summer School this year, one of the things he suggested was that when you have a controlled vocabulary, you should define resources for the terms in that vocabulary rather than having a fixed set of literal values.

For example, if you’re saying that the topic of a page is elephants you should use a triple like:

<> dc:subject <http://example.com/id/concept/animal/elephant> .

rather than one like:

<> dc:subject "elephant"^^xsd:token .

There are two advantages of using a resource here rather than a literal value:

-

You can associate other metadata with the term. For example, you can use SKOS to describe it and its associations with terms from other controlled vocabularies, giving it multiple labels in different languages, providing a description and examples and so on.

-

You can more accurately and easily associate multiple documents that use the same term. Of course you could always use string-based matching to pull together documents using the same subject, but that’s much more prone to error, and would leave you with less certainty about the results of your query.

What struck me, though, was that these arguments apply just as well to other typed values that we use within RDF. For example, say I wanted to describe the colour of my eyes. I could say something like:

<#me> eg:eyeColour "#695C3E"^^eg:colour .

But wouldn’t it be better to use:

<#me> eg:eyeColour <http://example.com/id/concept/colour/rgb/695C3E> .

The colour resource could have properties associated with it:

<http://example.com/id/concept/colour/rgb/695C3E>

a eg:Colour ;

skos:prefLabel "#695C3E" ;

eg:red "69"^^eg:hex ;

eg:green "5C"^^eg:hex ;

eg:blue "3E"^^eg:hex ;

eg:hue 42 ;

eg:saturation 41 ;

eg:brightness 41 ;

eg:pantone ... ;

... .

and so on. And if other people pointed to the same resource, a semantic search engine could give you a list of things of that colour.

And what about those numbers? Would it be better if I said:

<http://example.com/id/concept/colour/rgb/695C3E>

eg:red <http://example.com/id/concept/number/hex/69> .

and there was information about that resource:

<http://example.com/id/concept/number/hex/69>

owl:sameAs <http://example.com/id/concept/number/105> .

<http://example.com/id/concept/number/105>

a eg:Integer ;

rdf:value 105 ;

eg:divisor

<http://example.com/id/concept/number/3> ,

<http://example.com/id/concept/number/5> ,

<http://example.com/id/concept/number/7> ;

... .

and so on.

In fact, we already have identifiers for some of these resources. DBPedia inherits from Wikipedia information about (many) numbers and (some) dates. For example, check out what it says about the number 720 or the rather less helpful page on the year 1914.

What we lose is a certain level of ease of querying because the values that can be compared by SPARQL (say) are an extra step away. But it’s still doable so long as the resource has a rdf:value property holding the primitive literal for the type (one recognised by SPARQL). If I wanted to find married couples where the husband is younger than the wife, I could do something like:

SELECT ?husband ?wife

WHERE {

?husband eg:age ?husbandAgeResource .

?husbandAgeResource rdf:value ?husbandAge .

?wife eg:age ?wifeAgeResource .

?wifeAgeResource rdf:value ?wifeAge .

FILTER (?husbandAge < ?wifeAge)

}

One interesting aspect of these kinds of resources (and something Leigh promised to blog about too) is that they’re either infinite or have a large enough value space that it would be impractical to store all the information about them within a traditional triplestore. They could be made available as linked data easily enough since much of the interesting information about a colour or number would be derivable. But it might be difficult to provide a SPARQL end point for them. For example, consider:

SELECT ?number

WHERE {

?number eg:divisor <http://example.com/id/concept/number/3> .

}

ORDER BY ?number

LIMIT 10

There are already linked data spaces a bit like this floating around. The URIs defined by LinkedGeoData are infinite, given that it accepts any number of decimal places for latitude and longitude (technically it defines resources for circular areas rather than points). The RDF/XML that we’re producing for UK Legislation is generated on demand based on a date which, for each item, can be any date between 1st February 1991 and the current date.

What do you think? Is it mad to use resources instead of literal values? Where do you stop? How can queries be carried out over these infinite (or extremely large) sets of resources?