The HTML5 DOM and RDFa

One of the fundamental disconnects between HTML5 and previous versions of HTML is the way in which you answer the question “what is the structure of this page?”. Things that make use of that structure, such as RDFa, need to take this into account.

An example is the document:

<html>

<head><title>HTML example</title></head>

<body>

<table>

<span>Example title</span>

<tr><td>Example table</td></tr>

</table>

</body>

</html>

There are two different ways in which you might interpret the structure of this document. First, you might view the structure to be as it is written, with the <span> element as a child of the <table> element and therefore a tree that looks like:

+- html

+- head

| +- title

+- body

+- table

+- span

+- tr

+- td

Second, you might view the structure of the page to be the DOM as it is constructed by an HTML5 processor, which will move the <span> out from the table due to foster parenting, giving the result:

+- html

+- head

| +- title

+- body

+- span

+- table

+- tr

+- td

Which you view it as doesn’t really matter at this point, but it does when you start to introduce markup that infers information based on the structure of the page, such as RDFa. Let me introduce some RDFa markup to the document:

<html xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/">

<head><title>HTML+RDFa example</title></head>

<body>

<table about="http://example.com">

<span property="dc:title">Example title</span>

<tr><td>Example table</td></tr>

</table>

</body>

</html>

Now, if you view the structure to be as written, the <span> element is within the <table> element, and is therefore viewed as talking about whatever it is that the <table> element is talking about, namely http://example.com. So the RDF that you will glean from this page is:

<http://example.com> dc:title "Example title"

On the other hand, if you view the structure to be that constructed by an HTML5 processor, the <span> element is not within the <table> element, and is therefore viewed as talking about whatever the document is talking about, namely the document itself. So the RDF that you will glean from the page is:

<> dc:title "Example title"

This isn’t exactly a new problem. There has always been the possibility of Javascript embedded within a page changing the page by moving or inserting elements, making the page that a non-browser sees fundamentally different from the one that a browser sees. This has been used by SEO people and spam merchants to get search engines to direct people to pages which mutated into something different when they were actually visited by a browser. And this eventually lead to those people who cared about interpreting meaning from the structure of pages (ie search engines) to at least go some way towards evaluating the Javascript within the page in order to “see” the page as a human would.

So it’s not a new problem, but it’s still a problem.

For those people trying to define how RDFa is interpreted in HTML5, there are several unpleasant alternatives:

-

Define RDFa as operating over an HTML5 DOM. This would make things easy for Javascript implementations in as much as they can rely on being used with HTML5 DOMs, ie in HTML5 browsers. But it raises the implementation burden for other implementations, such as those based on XSLT or a simple tidy-then-interpret-as-XML approach: essentially every implementation will need to include an HTML5 parsing library.

-

Define RDFa as operating over a DOM, but leave the creation of that DOM as implementation-defined. This effectively passes the buck (“it’s not our fault that HTML5 processors will construct a different DOM from XML processors”) but makes it hard to test implementation conformance and for authors to know exactly how their page will be interpreted. For example, an implementation that constructed a DOM with randomly rearranged elements would be entirely conformant despite producing completely different triples from one that took the elements in the original order.

-

Define RDFa as operating over a serialisation, with precise wording that describes how that serialisation is mapped into a tree structure that is walked to process the RDFa within the page. This approach will prevent implementations that use other methods of constructing trees from being conformant; depending on how it’s defined that might include XSLT implementations and/or Javascript implementations and/or implementations that use standard (XML-based) libraries for parsing the documents.

Personally I lean towards the second of these: defining RDFa as operating over a DOM but placing no constraints on how that DOM is created. It leaves open the possibility of Javascript implementations to work on the DOM they see, which may be radically different from the one seen by other processors due both to HTML5 reordering of elements and the dynamic modification of the page through Javascript. (Several people use rdfQuery to do before-and-after parsing of RDFa within a page, turning browsers into semantic editors, for example.) But it also lets conformant implementations be constructed in other ways for implementation ease or user needs, supporting the use of XSLT through GRDDL and the static crawling of content with minimal processing.

Perhaps the set of permissible methods of DOM creation could be listed to prevent completely random processing, but I expect that it will be effectively limited through social and technological pressures. Implementations that build DOMs in random ways aren’t going to be as useful (to their users) as those that build them in expected ways; it’s also going to be far easier to implement RDFa processors using standard parsing libraries.

The approach is not without its downsides, of course. XSLT is similarly defined as operating over a tree model, with the question of how that tree model is constructed left to the implementation. Most processors decided to construct the tree using standard XML parsing, but famously MSXML would strip certain whitespace-only text nodes from the tree (unless you specified a parsing flag telling it not to), leading to incompatibilities and user confusion.

My guess is that the same kind of thing will happen with RDFa processors. It could very well be the case that an author will:

- check their RDFa in an RDFa validator that constructs a static HTML5 DOM, revealing one set of triples

- be confused when they then use a Javascript RDFa library within their page and get a slightly different set of triples because of some Javascript embedded in the page that changes its structure

- be further confused when a search engine that uses a tidy-and-interpret-as-XML approach gleans yet another slightly different set of triples and displays it in the search result

So if this approach were chosen, I would expect wording in the specification that required implementations to state the method they used to create the DOM (ie it should be implementation-defined rather than implementation-dependent) and that warned authors of the most likely causes of differences between implementations (such as tree modifications performed by HTML5 processors and Javascript within the page). I’d also like to see tools that take an HTML page and indicate the triples that it generates under different common DOM construction methods, so that authors can see the variation in how their documents might be interpreted.

Naming Properties and Relations

This post is about how to name properties and relations in RDF schemas. Or rather, about how different ontology developers use different conventions and how this can sometimes be confusing.

Part of the work that I’ve been doing over the last few months at TSO has been for OPSI, who want to provide information about UK legislation for reuse through an API as well as eventually through a new end-user service. The Single Legislation Service API is now available, in beta, if you want to take a look.

One way in which we’re providing information about legislation is using RDF/XML. An example is the Criminal Justice Act 1993 Section 67, for which RDF is available at http://legislation.data.gov.uk/ukpga/1993/36/section/67/data.rdf. For now, we’ve made the decision to not attempt to create any of our own ontologies for the RDF, but to reuse ones that are already out there.

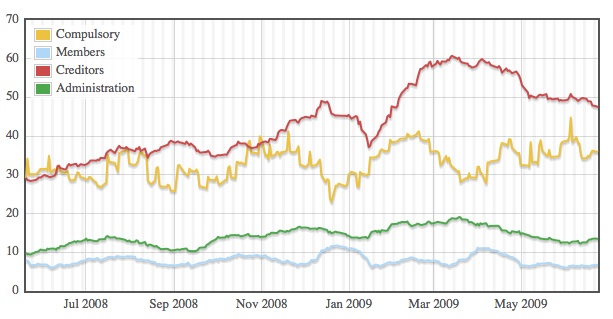

SPARQL & Visualisation Frustrations: Aggregation and Projection

Today, I’m going to moan about the lack of features in SPARQL that are necessary to do many kinds of data analysis and visualisation. Going from raw data, held in RDF, to data like

- the average traffic flow along the M5

- the total amount claimed by each MP

- the number of corporate insolvency notices published each day

cannot be done with SPARQL on its own. These calculations involve aggregation, grouping and projection which are planned for SPARQL vNext, but not here yet (at least, not in any standard way or in every triplestore).

Here’s the pretty graph to illustrate today’s rant:

On Resolvability

In my last post about RDFa and HTML I talked about how one of the gulfs that separates the HTML5 and Semantic Web communities is the attitude to the resolvability of property (and class) URIs.

I’m currently experimenting with introducing the ability to automatically locate information about properties and other resources that are referenced within triples to rdfQuery, so now is a good time, as far as I’m concerned, to look more closely at what the ability to resolve properties gives you and how to avoid problems if the property URI is (temporarily or permanently) unresolvable or resolvable to something new.

I’m going to attempt to answer:

- How do or might applications use property and class URIs?

- How can data and ontology publishers assist them in doing so?

- What should frameworks (such as rdfQuery) do to help application developers?

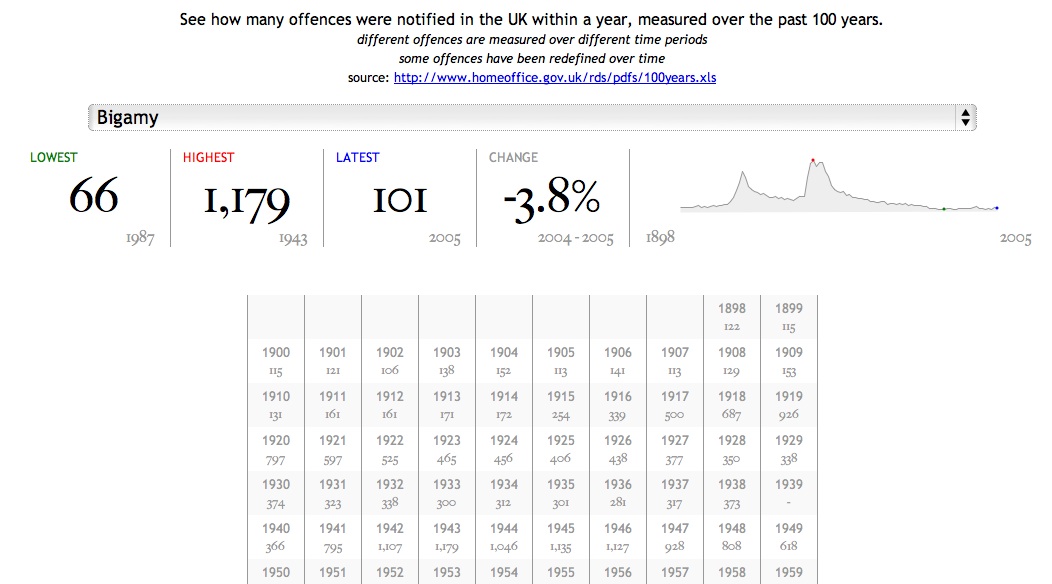

More Crime

I wrote previously about a visualisation using Home Office data to navigate around categories of offences. The second interesting set of data from the Home Office that I found, tucked away in a small link on a page about Crime Reduction Toolkits was a spreadsheet of recorded crime statistics between 1898 and the present day. Each column is a different category of offence (I won’t say class because they don’t map onto the Classes from the spreadsheet of notifiable offences).

This time I wanted to try out the jQuery sparklines plug-in to illustrate how crime notifications have changed over time. The resulting page is available at http://www.jenitennison.com/visualisation/crime.html; here’s a screenshot for Bigamy: